Japan: lost in (FX) translation

It was easy to overlook Japan’s election last weekend, amid the busy political calendar. However, it was not without incident. The incumbent Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) gained the most votes, as expected, though failed to achieve a majority – neither in its own right, nor as the previous governing coalition.

While the LDP’s popularity has been falling in recent years, amid higher inflation and political scandal, the local stock market has been rising (which has not usually been the case). Since the start of 2023, the MSCI Japan index has surged by almost a quarter on an annualised basis in Japanese yen terms, surpassing its late-1989 high earlier this year. However, momentum has faded in recent months, following a sharp sell-off in early August.

Has anything changed fundamentally?

Economic growth prospects remain subdued

The macro debate in Japan in recent years has been fixated on inflation, or more specifically its absence. This needn’t have mattered for investors if growth had been strong enough to offset static or gently falling prices, but it hasn’t. Total nominal growth – and growth in earnings per share – in Japan has been more sluggish than in other developed economies.

Moreover, the introduction of Abenomics in 2013 – a three-pillar strategy of using monetary policy, fiscal policy and structural reforms to stimulate economic growth – seemed to make little difference.

There have been tentative signs that these dynamics might have changed in the post-pandemic world. Headline inflation peaked at just above 4% (year-on-year) at the start of 2023, though much of this inflation was imported, rather than being a symptom of strong domestic demand. Wage growth has at least picked up a little, a sign that consumer spending could improve from here, but it is still negative when adjusted for inflation. Indeed, the IMF’s latest forecasts suggest that Japan’s sub-par growth may persist (figure 1).

Figure 1: Real GDP growth estimates by country

IMF actual and forecast data (annual average, %)

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, IMF

On a separate note, the trajectory of the Bank of Japan’s policy rate has attracted a lot of attention, but its remarkably low interest rates have been a consequence of low nominal growth, and not an attraction for stock investors. Japanese rates have now finally started to rebound, but with nominal growth still lacklustre they continue to signal economic weakness, not strength.

Gradual progress with corporate reforms

Japanese corporations have historically prioritised market share and stability, rather than shareholder returns. Businesses operate in a more conservative manner, M&A is relatively rare, and companies often hold ‘excess’ cash on their balance sheets (perhaps because of worries about falling prices and the ‘balance sheet recession’1 experienced by the private sector after that property bubble burst).

The ‘third arrow’ of Abenomics was specifically targeted at this structural lack of corporate competitiveness. The Stewardship Code was introduced in 2014 and the Corporate Governance Code in 2015, to better align domestic corporate governance practices with its Western peers (a point ironically overlooked by the Western economists who talked about a possible ‘Japanification’ of their economies). The Tokyo Stock Exchange also announced an unusual ‘name-and-shame’ strategy last year, which involved publicly announcing the listed companies whose price-to-book ratios were above one2 (the firms that did not make the list would be ‘shamed’).

Corporate governance metrics have in fact subsequently improved, but there is still some way to go. For example, the proportion of constituents in the MSCI Japan index who were engaged in cross-shareholding – an inefficient practice where firms strategically hold each other’s shares – declined to 36% in 2023 (from 43% in 2019), according to MSCI. Meanwhile, the MSCI US and Europe indices have respective figures of 0% and 2%. In addition, the share of companies where the board majority were not directors independent of management has declined over time to 71%, but this again is well above the US (3%) and Europe (5%) figures.

Stock fundamentals are unchanged

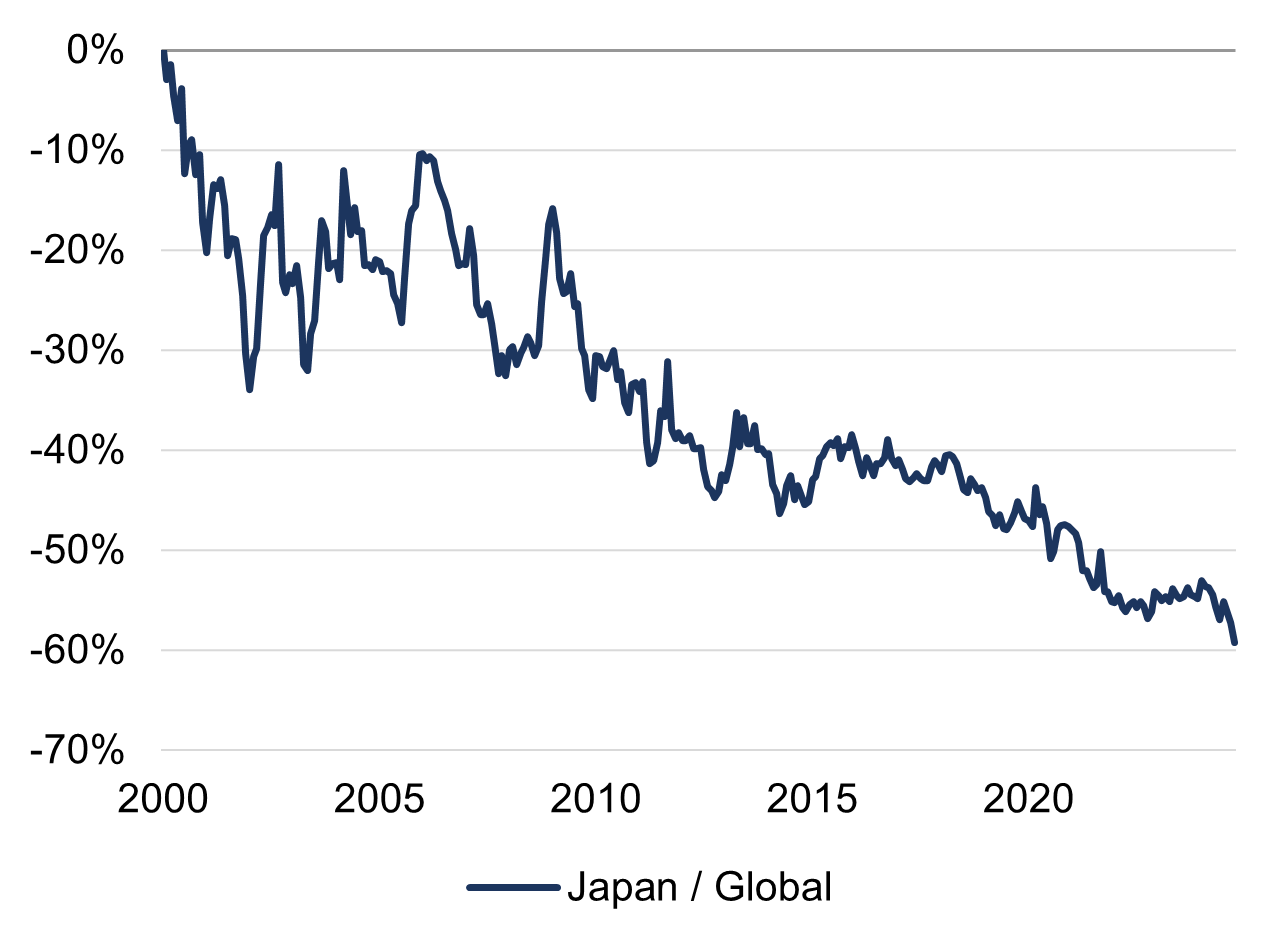

As noted, the domestic stock market has still soared since the start of 2023 in local terms. The weaker Japanese yen might have partly played a role, with export-orientated companies experiencing a boost to their earnings. However, that same currency weakness has also dampened foreign-based investors’ returns: global stocks (+22% annualised) have outperformed Japanese stocks (+14%) during that period in US dollar terms (figure 2).

Perhaps this common currency underperformance is justified. From a fundamental standpoint, the ongoing corporate reforms do not appear to have had a major impact yet. Return on equity (RoE) – a gauge of profitability – has been flat during the post-pandemic period at 9%. In fact, Japan’s RoE still ranks lowly, bottom of the major developed markets and just half the US figure (figure 3). Valuations are not compelling either. The MSCI Japan’s 12-month forward price-to-earnings ratio is at 15x, which is higher than more profitable regions such as continental Europe.

There are of course still many world-class businesses in Japan: for example, its consumer electronics companies remain internationally competitive. At the top-down level, however, there have not been any clear shifts in Japan’s overall profitability trends. And so, Japan’s importance in global portfolios may continue to carry little weight. Indeed, its prominence in economic and market debate is out of all proportion to its actual global share.

|

Figure 2: Relative returns

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, MSCI |

Figure 3: Return on common equity

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, MSCI |

Ready to begin your journey with us?

Speak to a Client Adviser in the UK or Switzerland

Citations

[1] This phrase was coined by economist Richard Koo. Following the dramatic decline in asset prices after the property bubble burst in 1990, liabilities became hugely important.

[2] Of course, listed companies do not directly control their own share price. The aim here is to incentivise companies to implement better governance, or risk losing their appeal with investors.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this blog constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.